RECOMMENDED: Exemplary female scientists and artists series - midnight lecture 38 🎻♀️⚗️

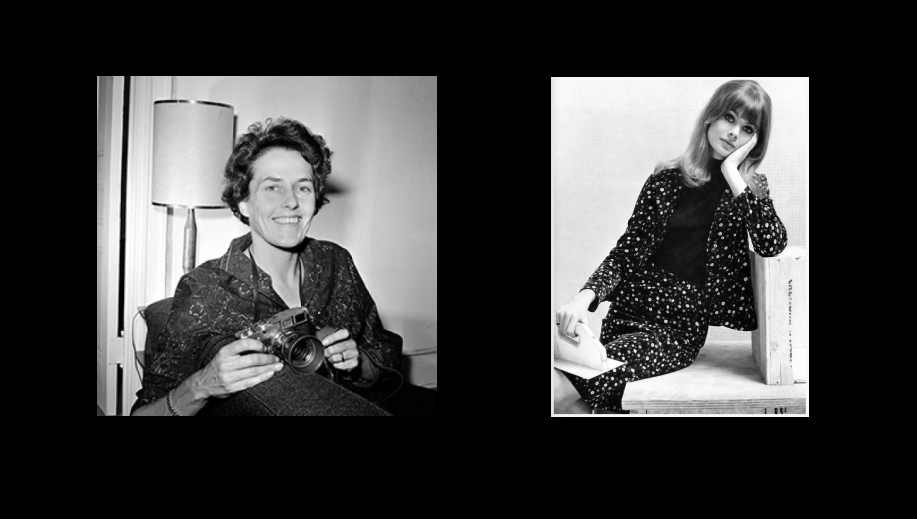

Inge Morath, Graz, Austria. As fluent in languages as she was in her relationships with the people whom she photographed. Like her colleagues who worked with the Magnum agency, she travelled extensively in Europe, North America and the Middle East. Originally, Magnum had employed her as an editor but she soon discovered that she was an even better photographer than writer. Inge Morath married the leading American playwright Arthur Miller.

In 1945, a Russian air raid forced Inge Morath to flee Germany by foot. She had moved to Berlin to study linguistics, but was drafted to work at a munitions factory alongside Ukrainian prisoners of war. Morath, 22 at the time, joined thousands of refugees, walking 455 miles to her parents home in Salzburg, Austria — an arduous journey that drove her to the brink of suicide.

In London, Inge Morath was on the lookout for someone who could teach her more about photography. She approached Simon Guttmann, once the director of the famous German photoagency Dephot, the first to practise the idea of the photo essay. Among the photographers who had worked for Guttmann at the time was Robert Capa—but she did not know that yet. In 1942 or 1943, Simon Guttmann had arrived in England and become adviser to the best English illustrated magazine of the time, Picture Post. He also founded his own agency, Report. Inge Morath said in her 1994 lecture that she approached Simon Guttmann to become his assistant. She showed him three contact sheets of her first films taken in Venice. He looked at them, not making the slightest commentary. Then he asked: “What do you want to photograph and why?” She mumbled something to the effect that she was mostly interested in people, in the variety of their lives, and she added that she was certain that after the life in the isolation of Nazism and war she felt she had found her language in photography, or at least the best way to express what she felt she had to say. He told her that she could start to work with him.

Morath wouldn’t become a photographer for another decade, but when she did, she refused to photograph war. “Her experience of the tremendous ugliness of what human beings can do to each other marked her for the rest of her life,” says Rebecca Miller, remembering her mother’s legacy on the event of her centenary. “It also made her really appreciate what art can do, which is sort of to make sense of life, to find coherence in an image that seems chaotic.”

After the Second World War, Inge Morath worked as a translator and journalist. In 1948, she was hired by Warren Trabant for Heute, an illustrated magazine published by the U.S. Office of War Information in Munich.

Morath eventually picked up a camera in 1951 in Venice. A brief period of rainfall had passed, and a gorgeous afternoon light flooded the city’s rain-soaked streets. Morath was captivated. She called up Robert Capa, urging him to send a photographer to capture the incredible light. Understandably, Capa responded by telling her it was too late to send a photographer, and that she should take the images herself. So she did.

Through contact with the photographer Ernst Haas, the trained translator Morath began working as a content writer for the "Magnum" photography agency in the early 1950s. She started taking photographs herself in 1951 and became a full member of the group in 1951. She took many photographs whilst travelling in Europe, China, North Africa and the Near East, but she also made portraits, snapshots and celebrity pictures – for example of Marilyn Monroe. She married the author Arthur Miller in 1962.

>>> (excerpts) ARTICLES IN DETAIL: magnumphotos.com, cosmopolis.ch, lempertz.com

Inge Morath: Her Life and Photographs, 2019

by Marco Minuz (Editor), Inge Morath (Photographer)

„Jean Shrimpton, one of the most iconic supermodels of the 1960s, embodied the effortless elegance of the era, redefining fashion and beauty with her striking features and natural charm. In 1964, during a photoshoot in Westhampton Beach, Long Island, New York, she was captured by the renowned fashion photographer William Helburn. Known for his bold compositions and ability to capture spontaneity, Helburn’s work reflected the youthful energy that Shrimpton brought to every frame. At the time, she was at the height of her career, gracing the covers of Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Elle, becoming the face of an era that embraced change, individuality, and a break from traditional beauty standards.

Shrimpton’s influence extended beyond her photographs; she was a trailblazer in the modeling world, paving the way for the rise of the ‘it girl’ phenomenon. Her relationship with British photographer David Bailey played a crucial role in shaping her career, with Bailey recognizing her potential early on and helping her become a leading figure in the Swinging Sixties. Unlike the highly stylized models of the previous decade, Shrimpton represented a fresh, modern look—minimal makeup, long, flowing hair, and a nonchalant attitude that captivated audiences worldwide. She famously caused a sensation at the 1965 Melbourne Cup by wearing a short shift dress, challenging the conservative fashion norms of the time and unintentionally igniting a global trend for the mini skirt.

"By the late 1960s, as the fashion industry shifted towards a new wave of models, Jean Shrimpton gracefully stepped away from the limelight, choosing a quieter life away from the frenzy of fame. She later settled in Cornwall, England, where she ran a hotel with her husband, Michael Cox. Though she distanced herself from the fashion world, her impact remained undeniable, with designers, photographers, and models citing her as an enduring inspiration. Decades later, her legacy lives on, representing a pivotal moment in fashion history when beauty became less about perfection and more about personality, confidence, and authenticity.” - History Glimpses

David Bailey : Jean Shrimpton / Platinum palladium print,

(„The relationship between the photographer and model reflected London as a global fashion capital and significantly influenced the visual language of the 1960s. Bailey and Shrimpton's professional and personal affinity...” - dellasposa.com)

Jean Shrimpton made a major contribution to fashion (article)

Jean Shripmton: My Own Story: The Truth about Modelling, 1965

Jean Shrimpton: An Autobiography, 1991

Jean Shripmton: The Truth About Modelling (V&A Fashion Perspectives)

- Kindle Edition -, 2019